How the Virus is Pushing America Toward a Better Future

The peak globalization bubble has finally burst and America has a chance to reinvent itself and realign how things work here with the best parts of our national identity.

Pessimism is the mood of the day, with 80 percent of Americans saying the country is generally out of control. Even before civil unrest and pestilence, most Americans believed our country was in decline, Pew reported, with a shrinking middle class, increased indebtedness and growing polarization.

It’s a dark hour, but the United States has a way of coming back, after struggling with itself, stronger than ever. As it did in World War II and the Cold War, America retains enormous sokojikara, or “reserve power,” as Japan political scientist Fuji Kamiya described it decades ago.

That power can be harnessed now that “the era of peak globalization is over,” as John Gray succinctly put it in the New Statesman. The good news is that the pandemic has shattered the mythical global village, weakening both economic and political ties between countries, including within the European Union. The days of global kumbaya are gone, as more people recognize that “free trade” has benefited the already affluent in large part at the expense of most people. Now is the opportunity for America to rebuild a more resilient economy and society, one structured around the people here more than on global capital flows.

Critically, the pandemic may bolster our ties to our communities and families. However bumbling the governmental response, Americans in this crisis have engaged in personal charity, much in evidence throughout the pandemic. There remains a natural proclivity to engage the virus as close to home as possible, providing precisely the kind of local solution, which, as the medical journal The Lancet notes, is critical to meeting the challenges posed by the pandemic. The sense of social responsibility has not disappeared. Despite attempts by some Trumpians to politicize the response, a vast majority of Americans, even Republicans, continue to wear masks and most Americans continue to socially distance.

Even faith, which has been suffering for years, could make a comeback. After all, the great pandemics of the Roman era, as William McNeil noted in his Plagues and Peoples, served as an enormous boon to Christianity, whose adherents devoted themselves to treating the afflicted while the pagans “fled from the sick and heartlessly abandoned them. Pestilence undermined pagan Rome, as historian Kyle Palmer has revealed, but it jumpstarted Christianity’s rise to dominance.

Today’s new “spiritual reawakening” may defy conventional forms, and become ever more a matter of personalized digital choice. As places of worship remain closed, virtual church attendance is booming, and according to Pew, a quarter of Americans say the pandemic has bolstered their faith, a finding also confirmed by Gallup. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the evangelical group Global Media Outreach has gone from reaching 350,000 people per day to upwards of 500,000 globally. A GMO leader told the Christian Post, “People are coming to us saying, ‘I need hope. Where can I find hope in the face of tragedy, anxiety, bankruptcy?’” He added, “When people are in pain, we offer encouragement and hope. They’re coming to us looking for answers.”

Having been stuck in lockdown for months, many of us have been reminded that, at the end, what really matters is family. We may only now being released from enforced contact with our closest relations, and even our roommates, and often painful separations from those who live farther away. “When society is facing a tremendous challenge or there’s a big uptick in suffering, people orient themselves in a less self-centered way and in a more family-centric way,” suggests Brad Wilcox, a professor of sociology and director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia.

The pandemic has weakened some of the traditional advantages of our biggest cities. The culture of the “jet-setter”, the bien-pensant who run our big corporations, universities, media companies and consultancy, no longer have to cluster in a handful of cities.

The psychological impact of this shift will persist. Almost a half year after the pandemic started, airports are still mostly “ghost towns”, with some taken over by wildlife and the loss of 100 million jobs globally. Travel will likely come back but in smaller numbers, and without the legions of business travelers who now can trek globally without leaving their screens.

Rather than the airport lounge, the new focus of work, as Al Toffler predicted decades ago, will be the home. Our lunge into telecommuting has reaped surprising productivity gains. Many companies, including banks and leading tech firms, including Facebook, Salesforce and Twitter, now expect a large proportion of their workforce to continue to remotely after the pandemic. A University of Chicago study suggests this could grow to as much as one third of the workforce. In Silicon Valley, it notes, the number reaches near 50 percent.

With two out of three tech workers now willing to leave San Francisco, big tech can get bigger while spreading talent and wealth more widely. Workers in denser communities, notes a recent Apartmentalist survey, now are far more likely to move than their counterparts in less crowded areas. The preference for lower-density housing has been amplified by the pandemic, not only here but in Europe as well.

In the process the pattern of economic concentration in the core, the great signature of Gotham, faces a rapidly diminishing appeal as evidenced by the increasingly empty New York towers, failed projects in San Francisco and downtown Los Angeles. Our core cities still can have a bright future, but one also less dominant. Given the mandate of social distancing — with its impact on crowded offices, elevators, and trains — dense cities will have to adjust to dramatically scaled back capacity at everything from offices, restaurants and parks.

With the reduction of what one writer describes as “insane crowds” of tourists, city-dwellers can rediscover the pleasures of urban life. They can thrive, as HG Wells predicted well over a century ago, as “places of concourse and rendezvous” and defy his projection that the cites would be dominated by the affluent, and childless, as places of “luxurious extinction.”

After Trump’s likely and well-deserved tossing out, his nationalist policy will not go away. Before 2016, and before the pandemic, much of the American establishment, from Michael Bloomberg to Joe Biden, largely embraced Beijing’s regime; some like former Senator Max Baucus have even become paid apologists. But with COVID-19 and the ensuing recession, the repression of Hong Kong and the mass incarceration of Muslims, China’s reputation has suffered a precipitous fall.

Some aspects of Trumpism will likely survive his own reign. Prominent Democrats like Andrew Cuomo have joined Trump in denouncing our ruinous dependence on Chinese medical supplies and there’s growing bipartisan concern about dependence on Beijing for high-tech gear. For all of Trump’s needless ruffling of feathers, Europe, Australia, Canada and Japan have all joined us in an emerging de facto “united front” against China.

To maintain a majority, Democrats, suggests former Indiana Senator Evan Bayh will be forced to adopt a more economic nationalist approach, particularly in the Midwest. There is already an emerging alliance between populists in both parties—Bernie Sanders and Joshua Hawley, for example—that oppose returning to the globalist fantasies of the Bush and Obama years.

Whoever wins in November will inherit an economy plagued by high unemployment. The job losses have been larger than the entire employment of metro New York, Los Angeles and Chicago put together. Over half of families with children have lost income. The Congressional Budget office suggests the economy could take a decade to recover.

Even in the best of times, back in February, our economy was failing many Americans.. Corporate mea culpas about racism and solidarity with Black Lives Matter may blunt criticism, but do not address the fundamental problem of diminished expectations, particularly in minority and working-class communities suffering continued economic distress and hopelessness. Unlike in the past, traditional liberalism has stopped producing benefits to the mass of workers.

Educated professionals, able to work from home, have weathered the pandemic better than working class people whose jobs require a physical presence. But the lockdowns have revealed our mutual dependence on millions of essential workers, whose jobs are often performed at great at great personal risk, in producing food, basic necessities and medical equipment as well as staffing our hospitals and operating the critical logistics chain. It’s one thing to call them “heroes” but another one to extend to them opportunities to build careers, get adequate pay, and health care, and the opportunity to own a business or home.

What workers in these sectors need is more investment in domestic industries. The good news is that America’s potential, even with the erratic Trump at the helm, has been widely recognized by investors, who have returned to our stock market far more than our rivals. Taiwan Semiconductor, for example, recently announced plans to build a $12 billion plant in Arizona. Our new economic focus needs to seek “reshoring” of industry on a massive scale. Despite the much ballyhooed consumer benefits of low-cost imports, the vast majority of Americans seem willing to pay higher prices that could come from moving production from China.

We are not a racial state with roots in a common past, as can be said of China, Japan, France, or Germany.

Where countries like China, Japan, France, and Germany can be described as states with roots in a common past, America, in its essence, is built on aspiration and a kind of reckless ambition. The American as described by the French-born 18th century traveler John Hector St. John remains a “new man”: innovative, independent, less bound by tradition or ancient prejudice. Even with racial and other barriers, no large country in history has been able to incorporate so many diverse peoples around a basic, if all too often violated, ideal.

We are either distinctly this kind of America, or simply a larger Europe without the charm and history. It is also hard to see how we can morph into a disciplined, homogeneous Confucian society, like Korea, China, or Taiwan, where people follow instructions with little question and accept the authority of the state.

Americans are different. They are not naturally obedient and have done best by taking chances. The real hero of this age is not the narcissist rich kid Trump, tech oligopolists or professional hysterics but entrepreneurs who are attempting to improve the material future by sending astronauts into space, working on electric and autonomous vehicles, developing new medical technologies and boring tunnels under our cities.

Such disruptive innovators, combined with the enormous physical expanse and wealth of our continental empire, represent secret sauce for America’s next resurgence. New companies historically take advantage of disruptions in part by accessing talent that would not have been available in better times. Many of what became great companies emerged in the Great Depression and subsequent deep recessions.

We can repeat this again. Our spirits may be down, our leadership inept and our confidence low, but we still possess that unique reserve power to confound doomsters both in the rest of the world and here at home.

This piece first appeared on The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is the author of the just-released book The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute — formerly the Center for Opportunity Urbanism. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin

Photo credit: digitized image of “American Gothic”, a painting by Grant Wood, in collection of the Art Institute of Chicago via Wikimedia in Public Domain.

Public Domain

Public Domain

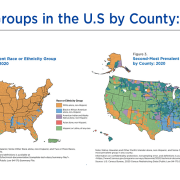

Ochlo, under CC 4.0 License

Ochlo, under CC 4.0 License