Feudal Future Podcast – Restoring the California Dream

Joel and Marshall discuss how we can restore the California dream, stopping the outflow of millennials and families headed for states that now offer better opportunity than California.

Joel and Marshall discuss how we can restore the California dream, stopping the outflow of millennials and families headed for states that now offer better opportunity than California.

On this episode of Feudal Future, hosts Joel Kotkin and Marshall Toplansky talk with Cullum Clark and Austin Williams about the future of cities and what it will take to build the new world.

From the ancient world to modern times, the class of small property owners have constituted the sine qua non of democratic self-government. But today this class is under attack by what Aristotle described as an oligarchia, an unelected power elite that controls the political economy for its own purposes. In contrast, the rise of small holders were critical to the re-emergence and growth of democracy first in the Netherlands, followed by North America, Australia, and much of Europe.

The pandemic has cut a swath through our sense of normalcy, but as has been the case throughout history, a disastrous plague also brings opportunities to reshape and even improve society. COVID-19 provides the threat of greater economic concentration, but also a unique chance to recast our geography, expand the realm of the middle class, boost social equity, and develop better ways to create sustainable communities.

Driven partly by fear of infection, and by the liberating rise of remote work, Americans have been increasingly freed from locational constraints. Work continues apace in suburbs and particularly in sprawling exurbs that surround core cities, while the largest downtowns (central business districts, or CBDs) increasingly resemble ghost towns.

This shift has made it more practical for individuals and particularly families to migrate to locations where they can find more affordable rents, and perhaps even buy a house. But such a pattern may be countered by investors on Wall Street, who seem determined to turn the disruption to their own advantage by gearing up efforts to buy out increasingly expensive single-family homes, transforming potential homeowners into permanent rental serfs and much of the country into a latifundium dominated by large landlords.

We are in the midst of what the CEO of Zillow has called “the great reshuffling,” essentially an acceleration of an already entrenched trend of internal American migration toward suburbs, the sunbelt, and smaller cities. Between 2019 and 2021 alone, a preference for larger homes in less dense areas grew from 53% to 60%, according to Pew. As many as 14 million to 23 million workers may relocate as a consequence of the pandemic, according to a recent Upwork survey, half of whom say they are seeking more affordable places to live.

This suggests that the downtown cores of U.S. cities will continue to struggle. Since the pandemic began, tenants have given back around 200 million square feet of commercial real estate, according to Marcus & Millichap data, and the current office vacancy rate stands at 16.2%, matching the peak of the 2008 financial crisis. Between September 2019 and September 2020, the biggest job losses, according to the firm American Communities and based on federal data, have been in big cities (nearly a 10% drop in employment), followed by their close-in suburbs, while rural areas suffered only a 6% drop, and exurbs less than 5%. Today our biggest cities—Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago—account for three of the five highest unemployment rates among the 51 largest metropolitan areas.

The rise of remote work drives these trends. Today, perhaps 42% of the 165 million-strong U.S. labor force is working from home full time, up from 5.7% in 2019. When the pandemic ends, that number will probably drop, but one study, based on surveys of more than 30,000 employees, projects that 20% of the U.S. workforce will still work from home post-COVID.

Others predict a still more durable shift: A University of Chicago study suggests that a full one-third of the workforce could remain remote, and in Silicon Valley, the number could stabilize near 50%. Both executives and employees have been impressed by the surprising gains of remote work, and now many companies, banks, and leading tech firms—including Facebook, Salesforce, and Twitter—expect a large proportion of their workforces to continue to work remotely. Nine out of 10 organizations, according to a new McKinsey survey of 100 executives across industries and geographies, plan to keep at least a hybrid of remote and on-site work indefinitely.

The shift of work from the office to the home, or at least to less congested spaces, threatens the strict geographic hierarchy of many elite corporations. Some corporate executives, like Morgan Stanley’s Jamie Dimon, are determined to force employees back into Manhattan offices, like it or not. It’s now a common mantra among like-minded executives, especially those connected to downtown office development, that workers are “pining” to return to the office. Some have even threatened employees who do not come back in person with lower wages and decreased opportunities for promotion, while offering to reward those willing to take the personal hit of coming back on-site every day.

Read the rest of this piece at Tablet.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Roger Hobbs Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

Photo credit: Steven Zwerink via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.

What started as a lark, then became an impossible dream—a conservative resurgence, starting in California—ended, like many past efforts, in electoral defeat. With his overwhelming victory in the recall election, California governor Gavin Newsom and his backers have consolidated their hold on the state for the foreseeable future.

The very idea of a recall vote seemed absurd at first in California, this bluest of US states. Yet Californians’ surprisingly strong support for the removal of Democratic governor Gavin Newsom has resulted in precisely that, with the vote scheduled for 14 September. This reflects a stunning rejection of modern progressivism in a state thought to epitomise its promise.

Some, like the University of California’s Laura Tyson and former Newsom adviser Lenny Mendonca, may see California as creating ‘the way forward’ for a more enlightened ‘market capitalism’, but that reality is hard to see on the ground. Even before the pandemic, California already had the highest poverty rate and the widest gap between middle and upper-middle income earners of any state in the US. It now suffers from the second-highest unemployment rate in the US after Nevada.

Today, class drives Californian politics, and Newsom is peculiarly ill-suited to deal with it. He is financed by what the Los Angeles Times describes as ‘a coterie of San Francisco’s wealthiest families’. Newsom’s backers have aided his business ventures and helped him live in luxury – first in his native Marin, where he just sold his estate for over $6million, and now in Sacramento.

California’s well-connected rich are predictably rallying to Newsom’s side. At least 19 billionaires, mainly from the tech sector, have contributed to his extraordinarily well-funded recall campaign, which is outspending the opposition by roughly nine to one.

There is little hiding the elitism that Newsom epitomises. In the midst of a severe lockdown, he was caught violating his own pandemic orders at the ultra-expensive, ultra-chic French Laundry restaurant in Napa.

Newsom insists California is ‘doing pretty damn well’, citing record profits in Silicon Valley from both the major tech firms and a host of IPOs. He seems to be unaware that California’s middle- and working-class incomes have been heading downwards for a decade, while only the top five per cent of taxpayers have done well. As one progressive Democratic activist put it in Salon, the recall reflects a rebellion against ‘corporate-friendly elitism and tone-deaf egotism at the top of the California Democratic Party’.

Much of this can be traced back to regulatory policies tied to climate change (along with high taxes). These policies have driven out major companies – in energy, home construction, manufacturing and civil engineering – that traditionally employed middle-skilled workers. Instead, job growth has been concentrated in generally low-pay sectors, like hospitality. Over the past decade, 80 per cent of Californian jobs, notes one academic, have paid under the median wage. Half of these paid less than $40,000.

Read the rest of this piece at Spiked.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

Some longtime Californians view the continued net outmigration from their state as a worrisome sign, but most others in the Golden State’s media, academic, and political establishment dismiss this demographic decline as a “myth.” The Sacramento Bee suggests that it largely represents the “hate” felt toward the state by conservatives eager to undermine California’s progressive model. Local media and think tanks generally concede the migration losses but comfort themselves with the thought that California continues to attract top-tier talent and will remain an irrepressible superpower that boasts innovation, creativity, and massive capital accumulation.

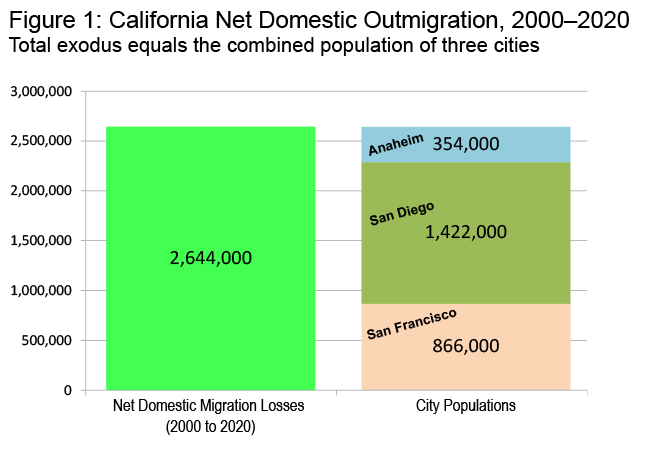

Reality reveals a different picture. California may be a great state in many ways, but it also is clearly breaking bad. Since 2000, 2.6 million net domestic migrants, a population larger than the cities of San Francisco, San Diego, and Anaheim combined, have moved from California to other parts of the United States. (See Figure 1.) California has lost more people in each of the last two decades than any state except New York—and they’re not just those struggling to compete in the high-tech “new economy.” During the 2010s, the state’s growth in college-educated residents 25 and over did not keep up with the national rate of increase, putting California a mere 34th on this measure, behind such key competitors as Florida and Texas. California’s demographic woes are real, and they pose long-term challenges that need to be confronted.

Source: Derived from U.S. Census Bureau Estimates

The state has suffered net outmigration in every year of the twenty-first century, but its smallest losses occurred in the early 2000s and the years following the Great Recession, when housing affordability was closer to the national average. Home prices have risen since then—and so have departures. Between 2014 and 2020, net domestic outmigration rose from 46,000 to 242,000, according to Census Bureau estimates.

The outmigration does not seem to have reached a peak. Roughly half of state residents, according to a 2019 UC Berkeley poll, have considered leaving. In Los Angeles, according to a USC survey, 10 percent plan to move out this year. The most recent Census Bureau estimates show that California started falling behind national population growth in 2016 and went negative for the first time in modern history last year.

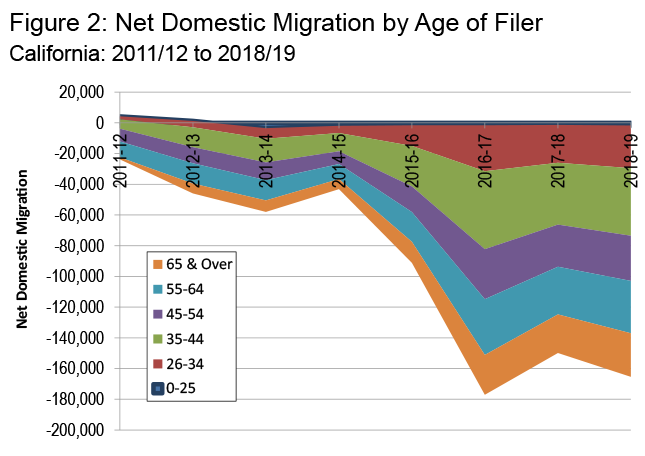

The comforting tale that only the old, bitter, and uneducated are moving out simply does not withstand scrutiny. An analysis of IRS data through 2019 confirms that increasing domestic migration is not dominated by the youngest or oldest households. Between 2012 and 2019, tax filers under 26 years old constituted only 4 percent of net domestic outmigrants. About 77 percent of the increase came among those in their prime earning years of 35 to 64. In 2019, 27 percent of net domestic migrants were aged 35 to 44, while 21 percent were aged 55 to 64. (See Figure 2.)

Source: IRS data

To be sure, the largest increase in net domestic migration was among those aged 65 and over. But the second-largest increase came in the 25 to 34 categories—with the state’s exorbitantly high cost of living the likely culprit.

Read the rest of this piece at City Journal.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston, a Senior Fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Winnipeg and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Photo: Beatrice Murch, via Flickr under CC 2.0 License

These are times, to paraphrase Thomas Paine, that try the souls of American optimists. A strain of insane ideologies, from QAnon to critical race theory, is running through our societies like a virus, infecting everything from political life and media to the schoolroom. Unable to unite even in the face of COVID-19, the country seems to be losing the post-pandemic struggle with China while American society becomes ever more feudalized into separate, and permanently unequal, classes.

The coronavirus pandemic has altered the future of American business. The virus-driven disruption has proved more profound than anything imagined by Silicon Valley, costing more jobs than in any year since the Great Depression. But there’s also good news, as Americans’ instinctive entrepreneurial spirit is driving growth and innovation: 4.4 million new business applications were recorded by census data in 2020, compared with roughly 3.5 million in 2019. Self-employment, pummeled at first, has recovered more rapidly than conventional salaried jobs, as more Americans reinvent themselves as entrepreneurs.

To be sure, the initial impact of the pandemic favored big chains and accelerated the already dangerous corporate concentration in technology—Amazon tripled its profits in the third quarter of 2020 and the top seven tech firms added $3.4 trillion in value last year. This in turn has made all business, as well as ordinary Americans, subject to manipulation by the handful of “platforms” that control the primary means of communication. Meanwhile, lockdowns drove an estimated 160,000 small businesses out of existence and left those that survived to face “an existential threat,” according to the Harvard Business Review.

Like pandemics of the past, the current one, according to Berkeley economists Laura Tyson and Jan Mischke, has already driven new investments in technology that could reverse the long-term decline in U.S. productivity. Low real estate prices could spark a return to street-level enterprise, even in places like Manhattan that have long been ultra-costly.

But the focus of opportunity is more likely to be found in the suburbs and exurbs, as well as in the middle of the country. The movement of populations away from the big urban centers started before COVID, but a recent study in CityLab notes that it has since accelerated in places like California’s Inland Empire, the Hudson Valley, and the New Jersey suburbs. Overall, according to demographer Wendell Cox, offices on the fringe have recovered far faster than those in the largest urban cores like Manhattan, San Francisco, Chicago, and Houston.

The geography of work has changed as well. Upward of 30% of those who plan to work remotely after the pandemic, notes a recent Upwork survey, plan to do so outside the house: in coffee houses, coworking spaces, or other office environments closer to home. This has created a new market for suburban office spaces, real estate investor Andrew Segal told me. He sees remote offices filling with workers who may be tired of working at home but do not want to go back to their long commutes. Segal has recently purchased properties in the suburban commuter sheds around Chicago, New York, Phoenix, and Colorado Springs. “The problem is called COVID, but it’s really about commuting,” suggested Segal, who is based in Houston. “People now know they can get their work done from somewhere else that’s easier to get to than Manhattan, downtown Houston, Chicago, or Los Angeles.”

Businesses are following the trend. Between September 2019 and September 2020, according to the firm American Communities and based on federal data, inner cities experienced nearly a 10% loss in jobs, while outer suburbs, exurbs, and rural areas fared far better. According to Jay Garner, president of Site Selectors Guild, companies are looking increasingly at smaller cities and even rural locations rather than in the big core cities. Indeed, seven of the top 10 midsize cities preferred for new investments include not just sunbelt boomtowns but heartland cities like Columbus, Des Moines, Indianapolis, and Kansas City.

Analysis by Zen Business this year found that the best places for small businesses in terms of taxes, survivability, and regulation were overwhelmingly in the South, parts of the Great Plains, Utah, and across the Midwest. Places like the Bay Area, New York, and Southern California crowded the bottom of the list. In some cities like San Francisco, even opening an ice cream shop has become subject to unendurable, endless regulatory reviews. Many heartland cities are exploiting this opportunity, with some offering generous bonuses to telecommuters from the coasts.

Read the rest of this piece on Tablet Magazine.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

Homepage photo: G. Keith Hall via Wikimedia under CC 3.0 License.

Last spring, the COVID-19 pandemic caused perhaps the worst job losses since the Great Depression. The decrease in the labor force participation rate — from 63.3% to 61.3% — has been steeper than that seen in the Great Recession and is among the largest 12-month declines in the post-World War II era, according to the Pew Research Center and federal labor data.