Inside The Sinosphere

Forbes.com

This piece was co-written with Hee Juat Sim.

Avis Tang, a cool, well-dressed software company executive, lives on the glossy frontier of China’s global expansion. From his perch amid tower blocks of Tianfu Software Park on the outskirts of the Sichuan capital of Chengdu, the 48-year-old graduate of Taiwan’s National Institute of the Arts directs a team of Chinese software engineers who are developing computer games for his Beijing company, Perfect World Network Technology, for the Asian and world market.

A glossy software office in Chengdu seems a long way from the images of centrally directed, belching factories seeking to dominate the global economy. But a close examination of the emerging Sinosphere–or Chinese sphere of influence–shows an economy that is globally dispersed, multinational and increasingly focused on the high-tech and service sectors.

Yet if Tang came to China to work for Interserv, a Taiwan game developer, he would see that the future of his industry–including its creative side–lies not only in the coastal cities but, increasingly, in those stretching across the vast Chinese interior. “In ten years perhaps all these cities will follow the path of Shanghai,” says Tang, as technology allows businesses that once had to situate themselves in coastal megacities to expand into the interior.

Widely considered one of the most “livable” of China’s big cities, Chengdu seems to Tang something of an incipient Silicon Valley. The area’s software revenues increased more than tenfold over the past decade, while an estimated 200,000 people are expected to be working in the city’s software industry by 2012.

Like many of his fellow managers at the sprawling park, home to over 800 foreign-owned companies, Tang is not a citizen of China. He’s from Taiwan and never set foot in the People’s Republic before 2001. His wife remains in Taiwan (Tang flies there every month or two to see her).

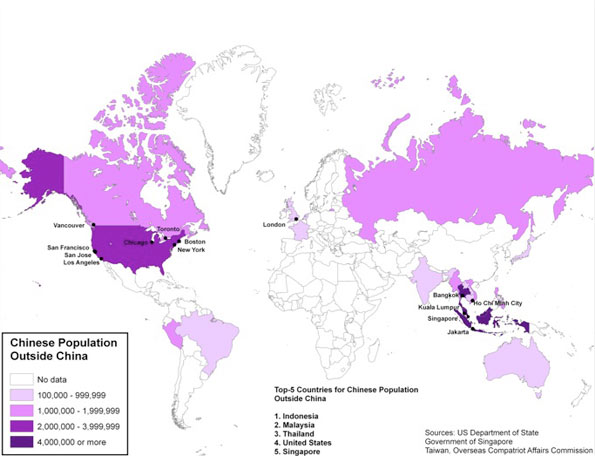

Chinese capitalism has relied on diaspora entrepreneurs like Tang. In this sense, the rise of China represents the triumph of a race and a culture. Indeed for most of its history China’s most important export was not silk or porcelain but people. To measure the rise of the Sinosphere, one has to consider not just China itself but what historian Lynn Pan has described as the “sons of the Yellow Emperor.”

The Sinosphere’s roots lie with the Han expansion into southern China during the Tang dynasty (618-907). By the 12th century, the newly Sinofied southern Chinese had started moving south. There they created trade-oriented colonies like Vietnam, Burma, Malaya and the island of Java. In the 1600s Chinese settlers overcame the aboriginal inhabitants of Taiwan, creating another powerful base in the South China Sea.

At its height, during the expeditions of the legendary eunuch Admiral Zheng Hein in the early 15th century, China’s maritime “sphere of influence” extended all the way to the Indian Ocean and beyond.

Although ensuing Chinese regimes pulled back from expansion and all but abandoned their scattered children, the colonies, particularly in Southeast Asia, survived. They developed business and industries suitable to their new homes, but also maintained their cultural heritage and language. After the Chinese Communist takeover of the mainland in 1949, the diaspora colonies retained their capitalist orientation. Many established trading operations and sent their children to the United States, Canada and Australia, where they enjoyed remarkable success.

Hong Kong, Singapore, Taipei, Rangoon, Bangkok and Jakarta can be seen as the original testing grounds for Chinese capitalism. In the past few decades North American regions such as Silicon Valley, Southern California, Toronto, Vancouver and New York-New Jersey have been added to the mix. Overall the entire overseas Chinese population has risen to nearly 40 million. Taiwan, which is de facto independent, is home to an additional 23 million, and Hong Kong and Macau, officially part of China but governed under different laws, boasts some 7.5 million.

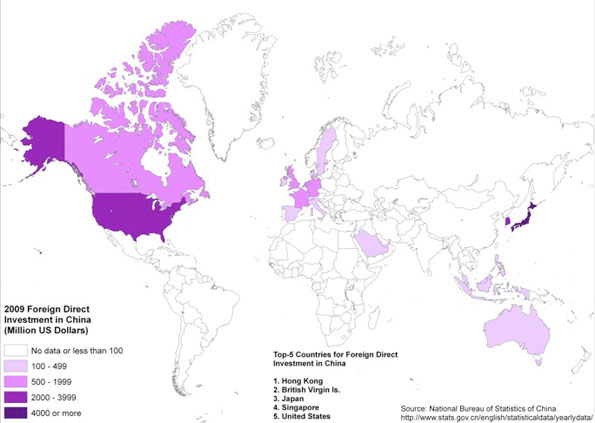

Even today the ties between overseas Chinese and their home country remain close. The original diaspora countries—including Hong Kong–remain principal sources of investment into China. Among the ten largest sources for inbound investment to the PRC are Hong Kong, by far the largest investor, fourth-ranked Singapore and ninth-ranked Taiwan. Each brings more investments into China than such major powers as Germany, France, India and Russia. The United States, home to the largest overseas Chinese population outside Asia, ranks fifth.

Other investments come from places like British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands and Samoa, which often act as conduits for investors who do not want to be too closely monitored. This seems to include many Chinese investors, particularly in Taiwan, who may not want too much scrutiny of their outlays into the PRC. This includes even Chinese government -owned firms such as China Mobile Communication Corp., which has established an investment HUB in the far away British Virgin Islands.

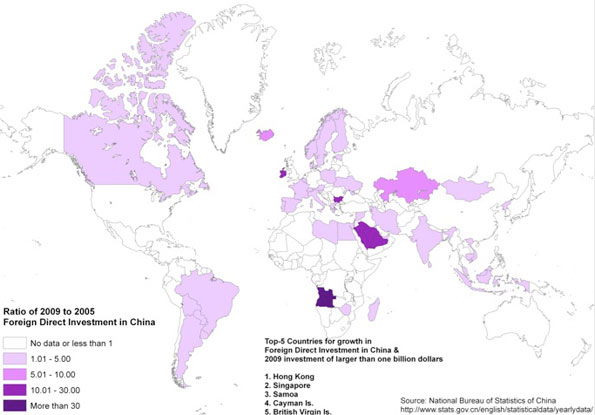

As China itself has become wealthier, financial flows from the diaspora have continued to increase. Hong Kong’s investment into China grew from $18 billion in 2005 to $45 billion four years later. Singapore’s investment surged from $2.2 billion to $4.1 billion in the same years. This has occurred while new investment from such powerhouses as the United States, Japan, Korea and Germany has stagnated or even dropped.

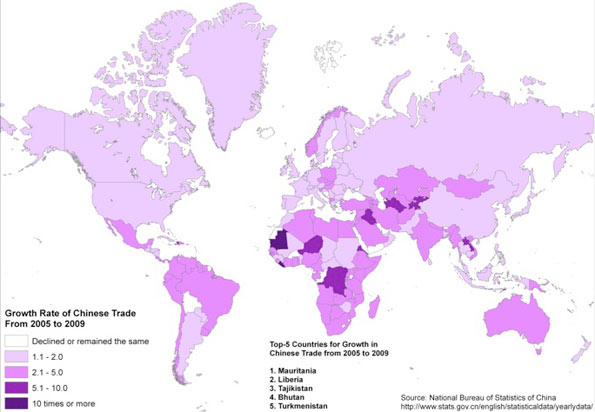

The second phase of the Sinosphere has been dominated largely by industrial projects, many of them financed or helped technologically by the diaspora. Much of trade, initially, was targeted to the rich consumer markets of North America, Europe and Japan. Between just 2007 and 2009 China’s share of world exports expanded from 7% to 9%.

But today the Sinosphere’s trade flow is shifting. An analysis of trade growth between 2005 and 2009 shows a significant change in focus away from advanced countries to the developing world. In the second half of the last decade, for example, trade with the United States, Japan, Germany, South Korea and the Netherlands grew by less than 50%. In contrast, commerce with key developing countries–including Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Mauretania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia Turkmenistan, Iraq and Laos–grew ten times. Trade with large emerging economies, notably Brazil, India, Mexico and South Africa, increased five times during the same period.

China’s thirst for resources is a big driver of this shift. Now the world’s largest car market and consumer of energy, China is in great need of oil, gas, and other natural resources. It also requires vast amounts of foodstuffs, notably corn and soybeans, for its increasingly urbanized population.

Two of China’s new trade thrusts follow historic patterns of expansion, the first being growing investment in the Mekong Delta and Southeast Asia (Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Malaysia). For 2010, Chinese invested $7.15 billion in energy projects alone in Myanmar. On the military side, this also includes moves by China to secure offshore islands for energy development, which is a potential source of conflict with Vietnam, the Philippines and Japan.

The second big expansion is along the old “silk road” connecting eastern China to the energy and mineral rich “ stans” of Central Asia. This shift enhances the importance of inland Chinese cities, such as Xi’an, Chengdu and Chongqing, which are natural entrepots for central Asian trade. Perhaps even more important may prove the role of Kashgar, which was designated last year as the Special Economic Zone. Sitting on the western edge of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Zone near the border of Tajikistan, the Chinese envision Kashgar as the main rail and air link to the stans. Recent disturbances by the local Muslim majority, however, could threaten these ambitious plans.

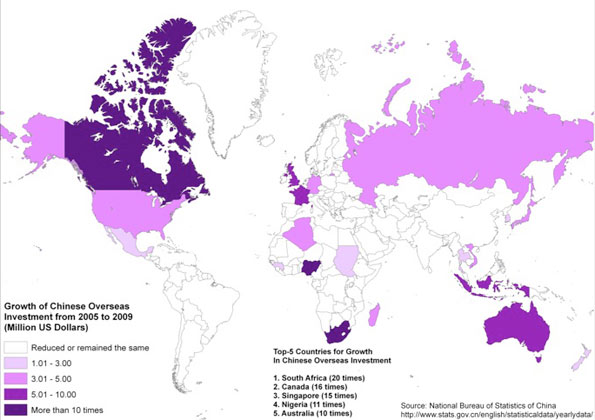

As China’s economy and wealth has grown, it has moved from being merely a recipient of inbound investment into a major exporter of capital. China’s outbound investment is growing much faster, rising 21% in just the past year; its overseas investment overall has grown from 53.3 billion in 2005 to 224.4 billion in 2009.

Although still the largest destination for foreign investment, the country has vaulted into the top four in terms of outbound outlays just behind the U.S., Japan and the U.K. It is not inconceivable that China could challenge the U.S. as the world’s top foreign investor.

The country’s investment strategy seems to be following two powerful trends. One has to do with the acquisition of resources to feed the Chinese industrial machine and its growing consumer market. This explains the rapid growth of investment into the Middle East, South America and Africa. Four of the five fastest-growing investment areas for large scale investments–South Africa, Canada, Nigeria and Australia–are all major commodity exporters. Chinese investment in these countries has been growing from three to five times as quickly as those in the U.S. or Western Europe.

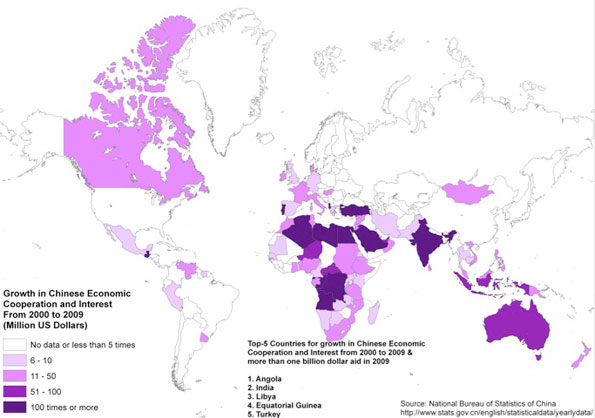

The second, less obvious, trend relates to the idea that these countries, with generally faster growing populations, represent the most lucrative future markets for Chinese exporters. This may be best seen in the rapid growth of Chinese government grants as well as the provision of interest-free and concessional bank loans, such as those provided by the government’s Exim bank, primarily to Chinese companies seeking to invest in developing nations, especially Africa, over the past decade. PRC financial backing for companies and projects in countries such as Angola, India, Equatorial Africa, Turkey, Egypt, the Congo and Algeria have grown over 100 times since 2005. Other key developing countries such as South Africa, Ethiopia, Somalia and Ghana all saw increases of tenfold or more.

These developments tell us something of the future of the Sinosphere. It will be largely funded by the Chinese and their diaspora, less focused on the West and more on developing countries, including increasingly those outside the traditional stomping grounds of Chinese entrepreneurs. The emerging Sinosphere is also likely to be somewhat less focused on manufacturing and more on services like real estate, finance and high-technology exports. This is partially due to the appeal, for manufacturers, of less expensive, more youthful countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam and Myanmar. Wages for manufacturing workers in the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia are now less than half of those in China.

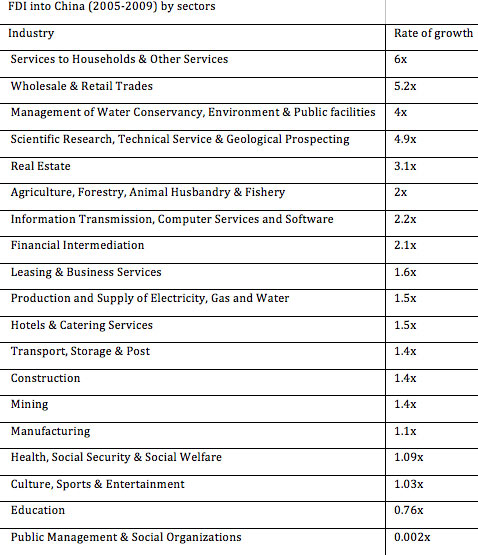

These shifts are already evident by looking at recent trends in inbound investment to China, much of it from the diaspora and tax havens. Between 2005 and 2009, for example, industrial investment fell from 70% to barely 50% in 2009. The total investment in industry has remained stagnant while dollars into scientific research have grown almost five-fold. We can expect more of this as China prepares to challenge America, Japan and other advanced countries in basic research. At the same time investment into real estate has tripled, while both software and financial flows have more than doubled.

All this explains the importance Chinese officials place on expatriates like the Taiwan-born Tang. In the 1980s and 1990s Taiwanese and Hong Kong firms spearheaded the development of China’s manufacturing prowess. Now the mainland leadership hopes that high-tech executives such as Tang will nurture and direct China’s leap into the first ranks of the global digital economy, with Perfect World’s Chengdu engineers epitomizing the future imagined by China’s aggressive regional officials. The fact that the company’s games are based largely on Chinese mythology makes the effort an even more natural fit. But Perfect World is not just looking at the Chinese or diaspora markets; it is also marketing aggressively to young gamesters in Europe and North America.

All this can be seen as a direct challenge to the long dominant software and entertainment industries of the West, heretofore largely unchallenged by China. In a world increasingly ’SINOFIED’ there may be huge potential for Sinosphere companies to move beyond exporting tangible goods, and increase their trade in ideas and culture to the rest of the world.

“We are well on our way,” Tang explains from his perch in Chengdu. “China’s move into this kind of business is just beginning.”