Peak Progressive?

In the minds of most progressives, as well as some horrified conservatives, California is the harbinger of America’s future. Governor Gavin Newsom sees his state as a model, claiming California is “the envy of the world” and the great bastion of social justice. “Unlike the Washington plutocracy,” he boasts, “California isn’t satisfied serving a powerful few on one side of the velvet rope.”

Yet it is ever more clear to ever more Californians that our state is becoming exactly the vast gated community Newsom warns about. As Ali Modarres showed in “The Demographic Transformation of California” (2003), the “shared prosperity” of the Pat Brown years were based on a broad-based economy spanning the gamut from agriculture and oil to aerospace and finance, software, and basic manufacturing. In contrast, the Newsom progressive model is built largely around one industry—high tech—which provides increasingly little opportunity for most Californians, and now shows disturbing signs of moving elsewhere.

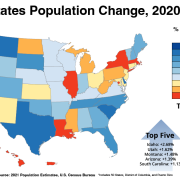

Current progressive policies are chasing key companies out of the state—including, just within the last week, tech giants Tesla, Hewlett Packard Enterprises, and Oracle, all of which are heading to Texas. But the real problem lies in the state’s fading appeal to outsiders. It is losing domestic migrants and, increasingly, losing appeal to immigrants as well. California retains many of its great assets—a huge concentration of technical talent, a robust grassroots economy, unmatched physical beauty, and a remarkably pleasant climate—but these are being increasingly squandered. The question now is whether Californians will challenge the status quo.

California Values

The progressivism that has emerged in California, unlike previous forms, is not a movement against entrenched power. It is an odd admixture of high-tech libertarianism with a quest for a more spiritual and, most critically, environmentally sustainable future. This amalgam of “cybernetics, free-market economics, and counter-culture libertarianism“ constitutes what British academics Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron described as “the California ideology.”

In the early days of the tech revolution, some imagined an almost utopian, communitarian society on the horizon—one that contrasted with the hierarchical structure found in Boston and eastern tech areas (see Annalee Saxenian, Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128 (1994)). The Californian author Stewart Brand, writing in Rolling Stone in 1972, predicted that when computers became widely available, everyone would become “computer bums, all more empowered as individuals and as co-operators.” It would be a new era of enhanced “spontaneous creation and of human interaction.” As Jaron Lanier pointed out in in Who Owns the Future? (2013), the “early digital idealists” envisioned a “sharing” web that functioned “free from the constraints of the commercial order.”

This utopian vision got a critical boost from the military and space programs (see Dirk Hanson, The New Alchemists (1982)), but even absent that help it held some relationship to reality. The tech economy in the suburbs south of San Francisco, as in aerospace-driven Southern California, allowed much of the workforce to buy homes, raise families, and enjoy a broad-base prosperity. The area, note two left-wing scholars, Manuel Pastor and Chris Brenner in Equity, Growth, and Community (2010), was also among the most egalitarian in the nation. It was a great place of opportunity for many—including immigrants, particularly from east Asia, who both set up P.C. board operations and increasingly launched larger firms on their own.

The Road to Oligarchy

The mythos of bohemian, enlightened capitalism helps explain why at the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011, anti-capitalist demonstrators held moments of silence and prayer for the memory of Steve Jobs, a particularly ruthless capitalist. Some even see the tech oligarchs, as the progressive writer David Callahan suggests in Fortunes of Change (2010), as a kind of “benign plutocracy” in contrast to those who built their fortunes on resource extraction, manufacturing, and gross material consumption.

Read the rest of this piece at American Mind.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

Gage Skidmore, used under CC 2.0 License

Gage Skidmore, used under CC 2.0 License D. Ramey Logan, used under CC 3.0 License

D. Ramey Logan, used under CC 3.0 License