How America Turned Into the EU

For many liberal Americans, the European Union is the perfect elite model: a non-elected, highly credentialed bureaucracy that embraces and seeks to enforce the environmental, social and cultural zeitgeist of the urban upper classes. It is, as the establishment Council on Foreign Relations puts it, a “model for regional integration”.

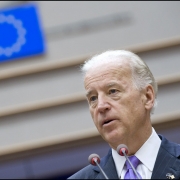

Now that “progressives” have returned to the White House, aping the EU has become a national policy. Taking his cue from his party’s Left, President Joe Biden has already sought to federalise many functions — from zoning to labour laws to education — that historically have been under local control.

But while Biden’s administration has been embraced by the Eurocrats, Americans would do well to consider the EU’s remarkable record of turning Europe into the developed world’s economic and technological laggard. Overall, nearly a third of Europeans consider Brussels an utter failure; half admit the EU’s pandemic response was inadequate. Indeed, while the American media was busy denouncing the US response to Covid under Trump as the “worst” in the world, the EU was showing them how it was done: of the 15 countries suffering the highest fatality rates, 13 are European, of which nine are in the EU — all worse than the US.

The US may always have had a “Federal Government”, but the notion of dispersed power gained approval from many on the Left only after President Trump’s election, as many Democrats looked to local government as a means of fighting back. Cheerleaders for Barack Obama’s imperial presidency, such as The New Yorker, started to embrace states’ rights with an almost Confederate enthusiasm.

But once the Democrats won back the House in 2018, the appeal of total central power became irresistible, with leading Democrats competing for who could most expand DC’s remit. Kamala Harris, now Vice President, demanded Washington give teachers across the country a federally funded five-figure pay rise, while Beto O’Rourke and Julian Castro sought to hand over local planning and zoning powers to the DC bureaucrats.

President Trump, for what it’s worth, had little interest in such issues — though even he made a point of trying to overturn states’ laws when it suited his agenda, particularly with the border wall and his attempts to crack down on radical education policies. In many ways, Trump’s authoritarian brand of Republicanism was always going to express an interest in an expanded federal role.

Yet in looking to expand federal power, Biden is picking up the mantle of President Obama, regarded by Republicans as one of the most prolific authors of executive power in US history. During its first six years, the Obama administration put forward more than twice as many major rules as George W. Bush’s government during the same period, focusing largely on issues such as climate change and immigration.

Of course, the notion of decentralised control — and the benefits associated with it — predates America. Ancient Roman cities enjoyed particular autonomy from central control, while the great Italian and Dutch cities of the early modern period developed extensive forms of self-government and, in some cases, functioned as independent states. Indeed, born out of Enlightenment ideals about limited government, the US Constitution lays out a system of dispersed power, creating in localities “the habits of self-government”.

In some cases, however, federal action was necessary; for example, to end the abomination of slavery and keep the Republic safe from European encroachments. And of course, some local governments continued to pass detestable laws, such as Jim Crow segregation in the South — though states also innovated in a more positive direction, providing models for other jurisdictions. For example, western states less tied to parochial ways of thinking — such as Wyoming, Utah, Idaho, Washington and California — introduced female suffrage well before the federal government. New York built the earliest welfare state, while my adopted home of California invested heavily in roads, schools, universities and technical training, leading to its remarkable boom in the late 20th Century.

States, as progressive Supreme Court Judge Louis Brandeis noted, were “laboratories of democracy”, places that experimented with policies that, when they were successful, would be adopted by others, and sometimes the federal government. In contrast, Europe’s bureaucratic meddling has served to keep wealth concentrated, as it has been for centuries, in places like Germany, the Netherlands and Scandinavia, while the south and east lag perpetually behind.

Read the rest of this piece at UnHerd.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

Homepage photo: European Parliament via Flickr, under CC 2.0 License.